For people living with diabetes, dietary management is a cornerstone of maintaining stable blood sugar levels and overall well-being. Among the countless dietary dilemmas they face, one question frequently arises: Is it better to consume fruit juice or whole fruit? In recent years, a growing body of epidemiological and nutritional research has shed light on this topic, offering evidence-based insights that can guide more informed dietary decisions for both individuals with diabetes and those at high risk of developing the condition.

First, let’s delve into the link between juice consumption and diabetes risk. A landmark study published in a leading nutritional journal tracked the dietary habits of over 100,000 participants for more than a decade. The results revealed that daily consumption of 250 milliliters (approximately one cup) of fruit juice was associated with a 7% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to those who rarely drank juice. What’s even more alarming is the impact of sugar-added juices—commercially produced juices that often contain high-fructose corn syrup or added sugars to enhance flavor. For these products, the associated risk of diabetes skyrocketed to 28%. This stark contrast highlights that the issue lies not just in the natural sugars of the fruit, but also in the added sweeteners and the way juice is processed. Such beverages can cause rapid spikes in blood glucose levels, straining the body’s insulin response over time and increasing the likelihood of insulin resistance, a key precursor to type 2 diabetes.

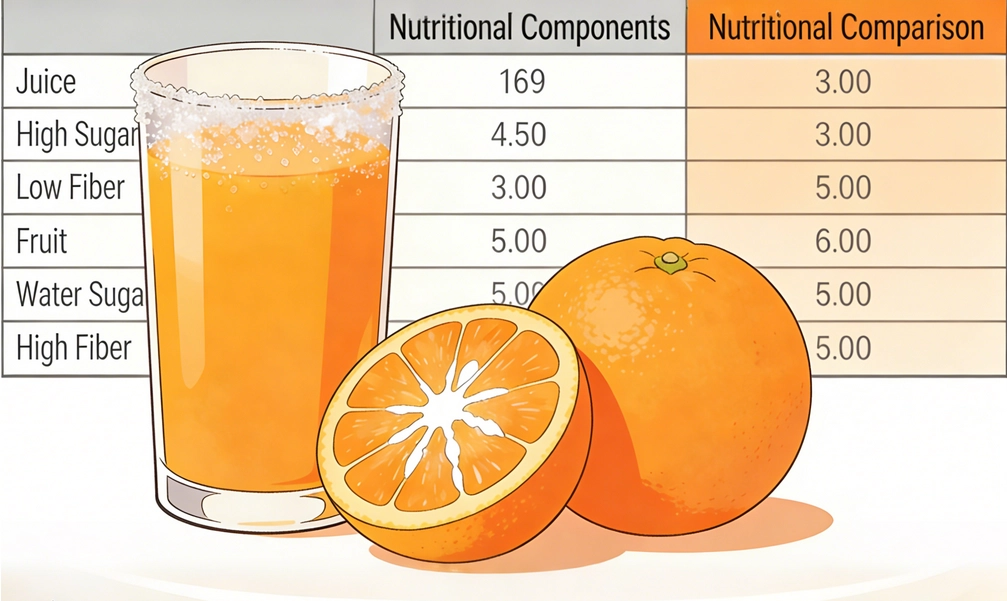

In striking contrast, whole fruit has been consistently linked to a reduced risk of diabetes, thanks largely to its unique nutritional composition. The same aforementioned study found that replacing just three servings of juice with whole fruit each week was associated with a 7% lower risk of diabetes. The primary driver of this protective effect is dietary fiber—a component that is largely removed during the juicing process. Whole fruits are rich in both soluble and insoluble fiber: soluble fiber forms a gel-like substance in the gut, slowing down the absorption of glucose and preventing sudden blood sugar surges, while insoluble fiber promotes digestive health and helps maintain a feeling of fullness. Additionally, whole fruit contains a balanced mix of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants that work synergistically to support metabolic health. For example, berries are packed with anthocyanins, which have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, while apples contain quercetin, a compound that may help regulate blood sugar levels. When we consume whole fruit, we also tend to eat less overall sugar compared to drinking juice, as a single cup of juice often requires two to three whole fruits to make—meaning we’re ingesting the sugar of multiple fruits without the fiber to mitigate its effects.

Yet, for many people, fruit juice remains a convenient and enjoyable beverage—especially for those with busy lifestyles or difficulty chewing whole fruit (such as older adults or individuals with dental issues). The good news is that the research offers a middle ground for juice lovers: consuming fresh, homemade fruit juice without any added sugars does not appear to increase diabetes risk. Unlike commercial juices, fresh juice retains most of the vitamins, minerals, and some of the soluble fiber from the original fruit (though insoluble fiber is still lost during straining). Moreover, homemade juice allows for full control over ingredients, ensuring no extra sugars or preservatives are added. However, it’s important to note that even fresh juice should be consumed in moderation. Experts recommend limiting fresh juice intake to no more than 150 milliliters per day for individuals with diabetes, as it still contains concentrated natural sugars that can affect blood sugar if overconsumed. Additionally, pairing fresh juice with a source of protein or healthy fat—such as a handful of nuts or a glass of unsweetened yogurt—can further slow down sugar absorption and stabilize blood glucose levels.

To sum up, the evidence is clear: when it comes to diabetes prevention and management, whole fruit is far superior to fruit juice. The dietary fiber and balanced nutrient profile of whole fruit provide crucial support for blood sugar control and metabolic health, while juice—particularly sugar-added varieties—poses a significant risk due to its concentrated sugars and lack of fiber. For those who simply cannot give up juice, fresh, unsweetened homemade juice is the safest option, but it should be consumed sparingly and paired with other nutrient-dense foods to minimize its impact on blood sugar. Ultimately, making informed dietary choices is not about restricting enjoyment, but about finding balance. By prioritizing whole fruits in our diets and being mindful of juice consumption, we can take proactive steps to protect our metabolic health and reduce the risk of diabetes-related complications. It’s also worth consulting with a registered dietitian or healthcare provider to tailor these guidelines to individual needs, as factors like age, activity level, and existing health conditions can influence optimal dietary recommendations.